Why Weight?

By: Amanda Kelly

Originally published in the Fall 2010 issue of Black & Tan Magazine

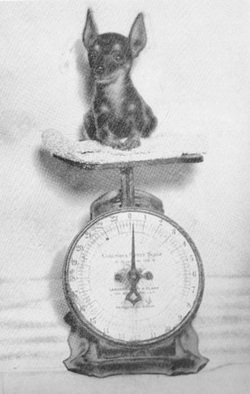

While breed standards in the rest of the world reflect an ideal height only for Manchester Terriers and both an ideal height and weight for English Toy Terriers, in North America the breed is and always has been judged according to weight. Wonder why? Well, the answer speaks directly to the original development of the breed almost 200 years ago.

The most convincing evidence of this can be found through examining writings on the breed and its forebearers over time. For example, early historical references from the late-18th and early-19th centuries make no mention of weight and, in fact, very little reference to size at all. As the sport of rat baiting became more popular from 1830 to the 1850s, however, weight became a common accompaniment to descriptions of black and tans and competitors in general.

The reason for this is likely one of competition rather than practicality. While breeds that were bred to go to ground were measured for height in order to ensure that they could fit into the den, breeds active in pit ratting were sometimes handicapped according to weight—meaning the size of the dog could have an impact on its owners’ pocketbook. In addition to straight matches where dogs were matched against the clock or against a set number of rats, proprietors often had matches where the skills of different sized competitors were compared proportionately. Weight handicaps were particularly popular in later years when finding enough rats became difficult.

The basic premise of a weight handicap is that the heavier the dog was, the more rats it had to kill. This makes sense, as a 5 pound dog killing 20 rats is a far greater feat than an 18 pound dog doing the same thing. Sometimes the handicap was a rat for every 3 pounds more a dog weighed; sometimes it was a rat for every one pound. The fastest dog killing their allotment was the winner.

According to one description "it was frequent to arrange a handicap where each dog had to kill as many rats as there were pounds in his weight, the dog disposing of his quota the quickest being the winner. For instance, a ten pound dog would only have to kill ten rats while Billy [who weighed 27 pounds] killed 27. This put rather a premium on small dogs and breeds were developed specially for this sport. The little smooth black-and-tan terriers of Manchester and the rough Yorkshire terriers were particularly good for this sport and a friend of mine owns a picture of three famous terriers ranging in weight from 5 ¼ lbs to 7 lbs." (Phil Drabble, The Book of the Dog, 1948)

Once established, the use of weight as a measurement would shape early dog shows as breed standards around the world initially based size for these breeds on weight only, with changes made to British standards following in the 20th century. In North America, however, the practice continued right through to modern day. Though the desired size range has changed over the years by a few pounds one way or another, the method of determining size has not.

As for the current weight limit, there is no clear reason why 22 pounds was selected. Historic breed standards have varied from a low of 18 pounds to a high of 25 pounds. Efficiency in the rat pit does not appear to be the issue as one of the most celebrated competitors in the history of the sport (not an MT, but a successful ratter nonetheless!) weighed in at 27 pounds. Documentation from this era in history is scattered at best, so we'll keep looking and perhaps one day we'll have an answer!

Sidebar:

Keeping Score

In the world of rat baiting, the number of rats a dog had killed at the end of a match was paramount—and a source of many arguments.

To quell fights, a simple method of determining if a rat was dead or alive was designed. Using chalk, a circle about the size of a dinner plate was drawn. Questionable rats were placed in the centre of the circle. The poor rat would receive a sharp whack to its tail with the edge of a piece of wood and, if this “encouragement” inspired him to wriggle out of the circle, he was pronounced alive. If he was too far gone or mortally injured to do so, he was pronounced dead – whether he agreed or not!

Originally published in the Fall 2010 issue of Black & Tan Magazine

While breed standards in the rest of the world reflect an ideal height only for Manchester Terriers and both an ideal height and weight for English Toy Terriers, in North America the breed is and always has been judged according to weight. Wonder why? Well, the answer speaks directly to the original development of the breed almost 200 years ago.

The most convincing evidence of this can be found through examining writings on the breed and its forebearers over time. For example, early historical references from the late-18th and early-19th centuries make no mention of weight and, in fact, very little reference to size at all. As the sport of rat baiting became more popular from 1830 to the 1850s, however, weight became a common accompaniment to descriptions of black and tans and competitors in general.

The reason for this is likely one of competition rather than practicality. While breeds that were bred to go to ground were measured for height in order to ensure that they could fit into the den, breeds active in pit ratting were sometimes handicapped according to weight—meaning the size of the dog could have an impact on its owners’ pocketbook. In addition to straight matches where dogs were matched against the clock or against a set number of rats, proprietors often had matches where the skills of different sized competitors were compared proportionately. Weight handicaps were particularly popular in later years when finding enough rats became difficult.

The basic premise of a weight handicap is that the heavier the dog was, the more rats it had to kill. This makes sense, as a 5 pound dog killing 20 rats is a far greater feat than an 18 pound dog doing the same thing. Sometimes the handicap was a rat for every 3 pounds more a dog weighed; sometimes it was a rat for every one pound. The fastest dog killing their allotment was the winner.

According to one description "it was frequent to arrange a handicap where each dog had to kill as many rats as there were pounds in his weight, the dog disposing of his quota the quickest being the winner. For instance, a ten pound dog would only have to kill ten rats while Billy [who weighed 27 pounds] killed 27. This put rather a premium on small dogs and breeds were developed specially for this sport. The little smooth black-and-tan terriers of Manchester and the rough Yorkshire terriers were particularly good for this sport and a friend of mine owns a picture of three famous terriers ranging in weight from 5 ¼ lbs to 7 lbs." (Phil Drabble, The Book of the Dog, 1948)

Once established, the use of weight as a measurement would shape early dog shows as breed standards around the world initially based size for these breeds on weight only, with changes made to British standards following in the 20th century. In North America, however, the practice continued right through to modern day. Though the desired size range has changed over the years by a few pounds one way or another, the method of determining size has not.

As for the current weight limit, there is no clear reason why 22 pounds was selected. Historic breed standards have varied from a low of 18 pounds to a high of 25 pounds. Efficiency in the rat pit does not appear to be the issue as one of the most celebrated competitors in the history of the sport (not an MT, but a successful ratter nonetheless!) weighed in at 27 pounds. Documentation from this era in history is scattered at best, so we'll keep looking and perhaps one day we'll have an answer!

Sidebar:

Keeping Score

In the world of rat baiting, the number of rats a dog had killed at the end of a match was paramount—and a source of many arguments.

To quell fights, a simple method of determining if a rat was dead or alive was designed. Using chalk, a circle about the size of a dinner plate was drawn. Questionable rats were placed in the centre of the circle. The poor rat would receive a sharp whack to its tail with the edge of a piece of wood and, if this “encouragement” inspired him to wriggle out of the circle, he was pronounced alive. If he was too far gone or mortally injured to do so, he was pronounced dead – whether he agreed or not!